[THIS IS AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE ORIGINAL GERMAN ARTICLE “ZU SCHÖN, UM ES ZURÜCKZUGEBEN” PUBLISHED ON THE SÜDDEUTSCHE ZETIUNG WEBSITE ON NOV. 5, 2018]

The Dutch Looted Art Commission does not want to restitute a work by Kandinsky. A similar case is occurring in Munich.

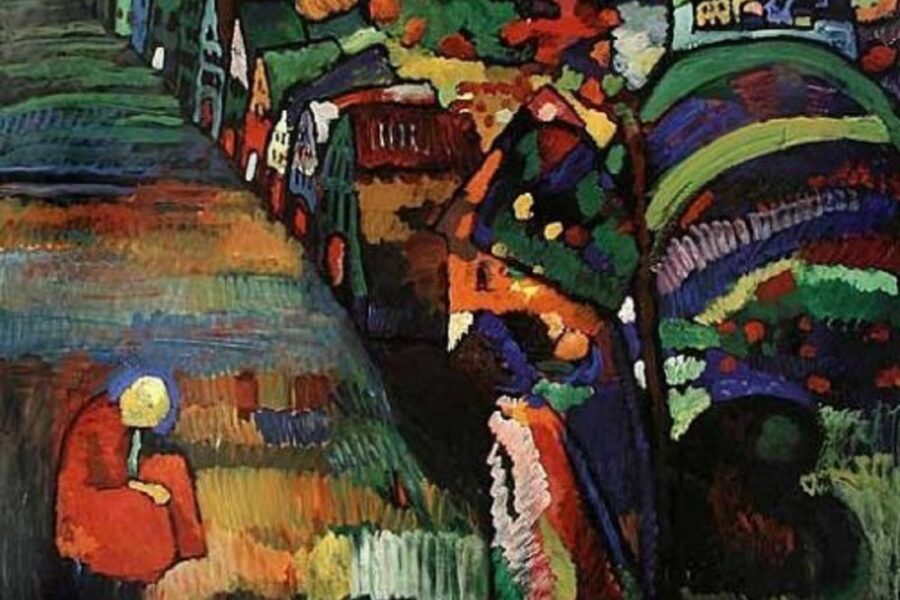

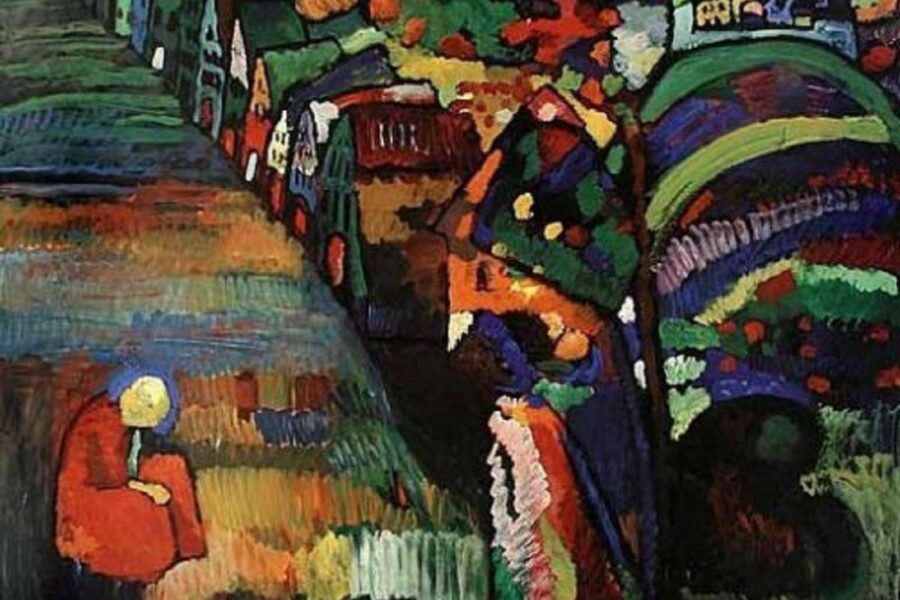

Munich is proud of its classical modernism in the Lenbachahus. It contributes a lot to the self-image of the city as an avant-garde and cosmopolitan metropolis. Ironically, one of Wassily Kandinsky’s key works in the museum, “The Colourful Life” of 1907, could be Nazi-looted art. The colourful, detailed work was auctioned in the fall of 1940 at a Nazi auction in occupied Amsterdam. It has been owned by the Bayerische Landesbank since the 1970s and is on loan to the Lenbachhaus. In 2017, heirs of the original Jewish owners claimed the work (SZ of March 4, 2017).

Since then, little has happened. After some back and forth, concerns on the part of the Landesbamk, and a threat of litigation by the heirs’ representatives, both sides agreed that the Limbach Commission, which meets in Germany regarding Nazi-looted art issues, may take the case. The fact that the Commission has not yet been called is explained by the fact that the players wanted to wait for the events in the Netherlands to be decided. Namely, the fact that Kandinsky’s “Picture with Houses” was already before the [Dutch] Restitution Commission responsible for looted art. This picture also once belonged to the collection of the Lewenstein family in Amsterdam and, like “The Colourful Life”, it ended up in the same auction in October 1940. This painting [“Picture with Houses”] was not acquired by an individual, unlike “The Colourful Life”, but by the then director of the Stedelijk Museum, for the ridiculous price of 176 guilders. Since then, Kandinsky’s “Picture with Houses” has been owned by the museum.

It will probably stay there for the time being, because the Commission has now rejected the request of the heirs. In contrast to Germany, decisions of the Restitution Commission are binding in the Netherlands. The rationale, however, leaves more questions open than answers.

At the time of the auction the original owner, Hedwig Lewenstein nee Weijermann, was dead. She had left her property to her children Robert and Wilhelmine, who had already left Holland. In Amsterdam, only Robert’s wife Irma Klein remained there. The couple was separated but not yet divorced. The German-Jewish actress had fled Germany before the Nazis and had tried to save her family as well. Her mother now lived with her in Amsterdam.

On the basis of the divorce proceedings, the Commission suspects that Irma Klein voluntarily put “Picture with houses” up for auction – in arrangement with her estranged husband, Robert. However, there is no evidence for this arrangement. Nevertheless, the Commission has concluded, from their own assumptions, that Irma Klein was allowed to dispose of the picture on her own and therefor today only her heir, and not the descendants of the Lewenstein siblings, could claim “Picture with Houses”. The heir of [Irma] Klein, however, [is said to have] no emotional attachment to the picture, and the painting is important for the Stedelijk Museum: so it should stay there.

This reasoning is so biased that the Commission thereby damages its credibility as an independent body. Even if their assumption that Klein gave up the work in October 1940 is true, the actress would have done so because of persecution and not because she was in need of money due to her upcoming divorce. In addition her husband and sister-in-law abroad had their hands tied anyway, they certainly had nothing to gain from a possible sale. The Commission ignores evidence that opposes [this alleged] family co-operation, including an attempt by an aunt of Robert and Wilhelmine to reclaim “The Colourful Life” for these two heirs after the war. This point will be very important for the German Limbach Commission, as well as the question of, on whose behalf an intermediary had delivered to the auction in 1940, the “The Colourful Life”, now situated in Munich.

The representative of the claimant, James Palmer, of the art research firm Mondex, calls the reasoning of the commission “biased”. He considers challenging the decision before a Dutch court. The spokesman for the Bayerische Landesbank, however, tells the SZ that his party will carefully examine the recommendation of the Dutch. It is “very detailed and carefully worked out”. Both sides would welcome the Limbach Commission to accept the Munich case soon.

It will be interesting to see how the Germans will behave in this story. The reclaiming of Kandinsky’s paintings also allows us to compare the work of the two commissions.