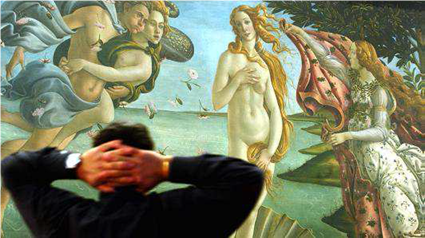

As Italy’s new government promises much-needed business and legal reforms to invigorate the country’s economy, experts have flagged one area in dire need of change: Italy’s art and antiquities export market. While the country holds a treasure trove of art dating back to the Renaissance and earlier, tough regulations governing the movement of “national treasures” have stifled its market, which is dwarfed by the art-world hubs of New York and London. Franco Origlia | Getty Images A viewer admires the ‘Birth of Venus’ by Sandro Botticelli, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. “The value of the art market in Italy is a small portion of the value in the U.K., whereas the quantity of art in the two states is exactly opposite,” said Massimo Sterpi, a Rome-based lawyer specializing in the art industry, who has co-edited a book called “The art collecting legal handbook.” Sterpi said he and his colleagues were lobbying the new Italian government—sworn in under Prime Minister Matteo Renzi this February—for changes to the laws governing the market. Read MoreEurope’s recovery depends on Renzi’s Italy Under Italian law, any object designated a “national treasure” cannot leave the country permanently—it can only be exported temporarily, for a maximum of 18 months. Even if an object is not a national treasure, official approval is required for it to leave Italy, even temporarily, if it over 50 years of age. “I’m totally surprised that Italy made so much harm to itself by passing these kind of laws and making everything so complex, rather than being the natural top art market in the world,” Sterpi told CNBC over the phone. “We did everything possible to make our markets very weak and we succeeded. There is so much scope for improvement, we hope some innovative government can come to understand one of the biggest industries we have, and help develop a world-class art market.” Read MoreArt and culture stories from CNBC James Palmer, a consultant at Mondex Corporation—which helps in the recovery of unclaimed property, including art—said a large amount of artworks in Italy are considered national art treasures, which therefore cannot be exported. “This logically has a negative effect on the art market,” he told CNBC over email. “The Netherlands, for example, also has a short list of artworks that cannot be transported, but the list in Italy is far longer.” What defines a ‘treasure’? Most countries take measures to protect national treasures, and European Union (EU) member states are entitled to do so for items of artistic, historic or archaeological value, due to an exemption clause in the treaty on the free movement of goods. As EU countries are allowed to define for themselves what constitutes national treasures, and exactly how they should be treated, wide variations in practices exist. Italy’s definition of a treasure is far more expansive than in countries like the U.K., France and the Netherlands, and its protection measures much stricter. “In Italy, it is impossible to export artworks in this (national treasure) category. So yes, it is an effective means of preserving art works. However, by hampering the free market, it can certainly have a negative impact on private collectors,” said Palmer. Read MoreItaly auctions off luxury cars… on eBay In the U.K. and France, for instance, officials only have the power to prevent an object’s export for a limited period of time, after which it can go abroad. The length of the export ban is decided on a case-by-case basis in Britain, and is set at a maximum of 30 months in France, although it is subject to renewal. In addition, while Italy requires approval for any object older than 50 years to leave the country, both France and the U.K. have minimum price thresholds below which permission is not needed. In the U.K., for example, a basic threshold of £34,300 ($57,655) for items going outside the EU applies. Heritage Images | Getty Images View of the Grand Canal by Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto, in Florence’s Uffizi gallery. Philip Hoffman, chief executive of the Fine Art Fund Group, an art investment advisory firm, said export restrictions meant works by Italian “old masters” like Canaletto and Bellotto sold for only 25-50 percent of their true value. “Nobody bothers to sell because it is too depressing… collectors are a bit stuffed,” he told CNBC over the phone. A pair of Venice landscapes by Canaletto sold for £9.6 million in London in December last year. However, according to Clare McAndrew, the founder of Arts Economics, no Canaletto has sold in an Italian auction since 2007, when one went for just under $500,000 in Milan. “I have studied the art trade in Europe very closely for the last 15 years, and whenever I’m describing what not to do to have a successful and healthy art market, I use the case of Italy and its regulatory system,” McAndrew told CNBC via email. Hoffman said the market for Italian work over 50 years of age currently stood at “practically zero,” with the total Italian market worth just under 390 million euros ($538 million) in 2013. He forecast that the liberalization of export rules could see Italy’s art industry explode to over $10 billion per year—a hefty addition to a global industry worth $55-60 billion annually. Read MoreArt sales top $64 billion: Sotheby’s As evidence, Hoffman pointed to the healthy market for contemporary Italian art. Unhampered by the need for export permits, this is worth $300-500 million a year. An auction of modern and contemporary art held by Christie’s this month in Milan generated sales of 9.7 million euros. “The Italian market for contemporary works is incredibly strong… the market has just rocketed,” he said. He doubted however whether this success would lead to rapid changes to export laws. “Most of these changes will take 10 years at the least,” Hoffman warned.