Tracing the familial history and link to the Levie art collection

“My parents were German, and even though we lived in The Netherlands, our culture was a German culture. Nazism, was an anomaly… ”

Born and raised in Berlin, Dr. Albert Heppner was a Jewish-German art historian and art dealer. As the son of an art dealer, Albert was immersed in the art world at a young age, and in 1924 earned his doctorate in art history from the University of Berlin where he developed his passion for Dutch masters. Once he completed his studies, in 1925 Albert gained professional experience through an apprenticeship at the Amsterdam-based gallery of the renowned Jewish art dealer, Jacques Goudstikker. With expertise in the Golden Age of Art in The Netherlands during the seventeenth century, Goudstikker was an influential mentor to Albert who returned to Berlin well-prepared to start his own art dealership after his apprenticeship ended in 1927.

By the early 1930s, Albert had a well-established reputation as an academic. However, the worsening political situation in Germany compelled Albert and Irene to flee to Holland for their safety. Shortly after arriving in Holland, they had their first and only child, Max, in 1933 and they soon settled in a small apartment in Amsterdam where Albert ran his art dealership in the basement, which doubled as a stock room. With some hired help, he successfully and discretely transported his paintings from Berlin to Amsterdam on a moving truck, all under the watchful eye of the Nazis. Unfortunately, antisemitism and the Nazi party began to take over Amsterdam as well, forcing Albert to take his business underground and to deal only with trusted contacts. While the terrible circumstances restricted Jewish persons from participating in civic life, there were some programs that allowed Jewish people to work or volunteer their time to Jewish community initiatives. Eventually, Albert began giving lectures in art appreciation at the Dutch National Gallery (Het Rijksmuseum), where he met and befriend Sam Bernhard Levie, and his wife, Sara de Zwarte (1899-1943).

Sam was a successful textile merchant and an avid art collector and was so touched by Albert’s kindness and passion for art that he bequeathed his entire art collection to Albert in his Will. However, in 1940 the Levies sold their paintings under duress to escape the Nazis through whatever financial means was possible. Tragically, in 1943, Sam and his wife died in an extermination camp in Sobibor, Poland. They had no children, and neither Albert nor his wife were aware of Sam’s Will. In 1942, Albert, Irene, and Max had fled to the countryside, and after a failed attempt to reach the free zone in France, they were taken in by a farming family who converted a small “chickenhouse” to a living space that just barely contained the family of three, and another Jewish couple who had been on the run with their teenage son.

Albert passed away suddenly in 1945, just after the war, and soon after Irene and Max had immigrated to the United States. In 1950 Irene visited her notary, who by coincidence was the same notary who had registered Sam Levie’s Will. This was the first moment that Irene was made aware of her heirship to the Levie’s property. After Irene’s passing in 1997 ownership of the Levie’s art collection was passed down to Max. “It took a lot of work and persistence to finally restitute the paintings,” Max said, reflecting on how a team of dedicated and creative Mondex researchers, administrators and lawyers made the restitution possible.

The Despoiled Artworks

Mondex research led to the identification and location of three of the despoiled paintings in the Levie art collection:

Copy after Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde (1638-1698), Amsterdam Town Hall, 1668

oil on canvas

75.5 x 91 cm

Adam Willaerts (1577-1664), Fantasy River Landscape with Figures and the Buurkerk in Utrecht. 1630

oil on panel

69.8 x 99.2 cm

Peeter Sion (c. 1620 – 1695), Vanitas Still Life, c.1637

oil on canvas

56.6 x 44.5 cm

After the war, the Dutch State Collection took possession of two of the paintings, “Amsterdam Town Hall” and “View of a Dutch Harbour” unaware of the bequest to the Heppners. Decades later, in 1998 the Office Origins Unknown was mandated to conduct provenance research for more than 4,000 objects in the Dutch State Collection. Several years into their research, the organization concluded that the paintings by Berckheyde and Willaerts were originally owned by Sam Levie, but incorrectly concluded that he was an art dealer, which meant that the sales of the paintings could not be considered involuntary unless evidence could prove they occurred under duress. Research later conducted by Mondex demonstrated that Sam was never registered as an art dealer and successfully established that the Office Origins Unknown erroneously categorized Levie as an art dealer. The error apparently arose from the Office’s use of an ambiguous post-war source, which suggested that Levie dealt commercially with art in 1925. In March 2014, the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, approved the restitution claim.

Research continues for other despoiled artworks in the Levie collection, and as our search for these artworks continues, we hope that by sharing Max’s story we will help to shed light on the importance of Holocaust art restitution.

What despoiled art can teach us

“I don’t want to have this feeling of incompleteness, that something’s missing— can we manage two feelings at once? … to be satisfied and still have somewhere in the back of your mind, something is still not complete…”

In a recent interview Amichai spoke candidly about his experience during the Holocaust, and about his feelings that have evolved over the years. In his poem below Max addresses the etymology of the German word “Wiedergutmachung” (“restitution”) to express the incomprehensibleness of the concept that to “make things good again” through some act or thing, is impossible, although there is some satisfaction to restitution itself, Max explains. Importantly, the restitution of despoiled art can help us learn about the Holocaust through the lens of art history; it can also give us a deeper understanding about museums and other institutions of culture and history.

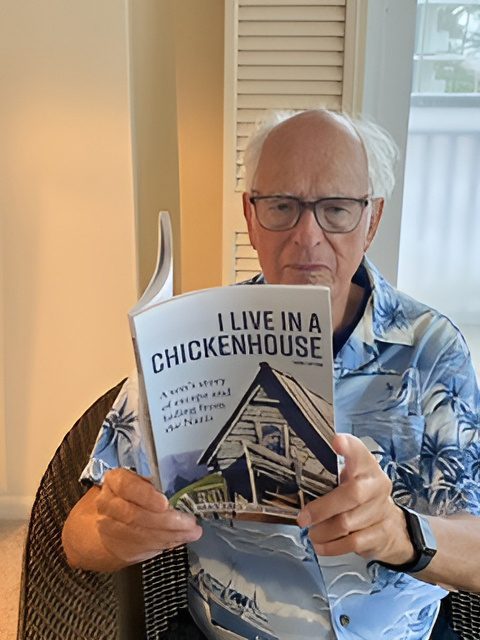

After the passing of his parents, Max became the heir of the Levie art collection. Today, Max is a retired U.S. Department of Agriculture public information specialist, currently based in Florida. The return of the three paintings mentioned above is very important for Max who, now in his nineties, continues to be passionate about sharing his Holocaust survival story. Max has authored several books, including his childhood memoir, “I Live in a Chickenhouse,” which can be read in tandem with “The Submergers,” pieced together from his father’s memoirs. Together, these books convey different vantage points from the same family experience of the Holocaust. The books are available on Amazon.

Max continues to share his story and raise awareness about the Holocaust in other ways: recently, his experience was explored with other survivors in a museum exhibition, which was featured in a New York Times article in 2024.

Mondex is currently supporting Max to travel and share his story through school presentations organized by The Morse Life organization, who has set up a program called “Holocaust Learning Experience.” Max’s poem appears below.

Wiedergutmachung

You can’t erase the past, Wieder.

Then was then. You killed then.

You trounced and trampled and burned

Until the past became a blight.

You can’t bring back the Gut, Wieder.

The good is gone. Good people dead.

Good life destroyed. Good times ended.

The good past can’t be recalled.

You can’t undo your Machung, Wieder.

The horror, the fear, the anguish.

Your Machung is a legacy of shame

That can’t be cleansed by another Machung.

You can relieve the present, Germans.

But in your arrogant stance

You think some money tossed at Jews

Can make everything Wieder Gut.

All can now be “Suss und Gut” you think.

And you won’t have to search your conscience

Why you hurt and maimed and killed so much

That nothing EVER will make it Wieder Gut.