[This is an English translation of the original French Article “Après 80 ans, un Chagall rendu à ses propriétaires” on Le Quotidien de l’Art on February 22, 2022.](https://www.lequotidiendelart.com/articles/21319-apr%C3%A8s-80-ans-un-chagall-rendu-%C3%A0-ses-propri%C3%A9taires.html)

By Jade Pillaudin Edition No. 2332 February 21, 2022 at 9:17 p.m.

© Adagp, paris 2022.

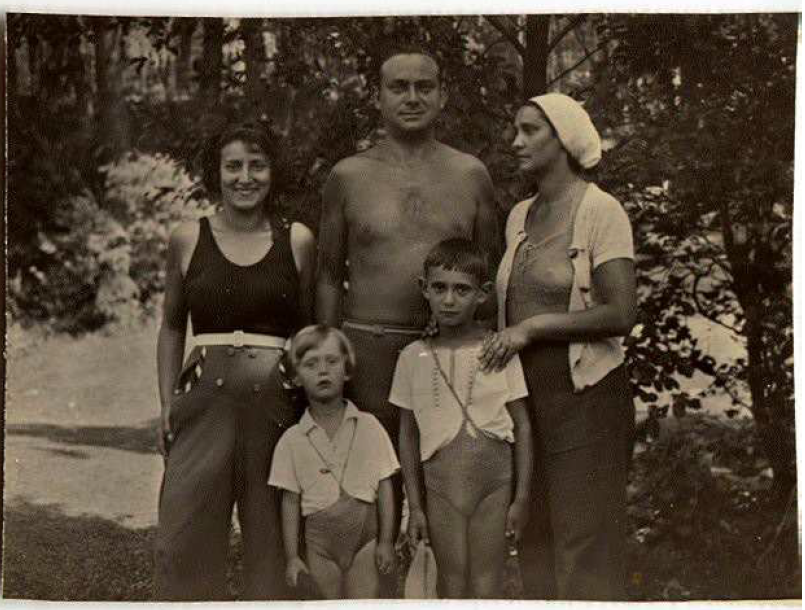

© DR.

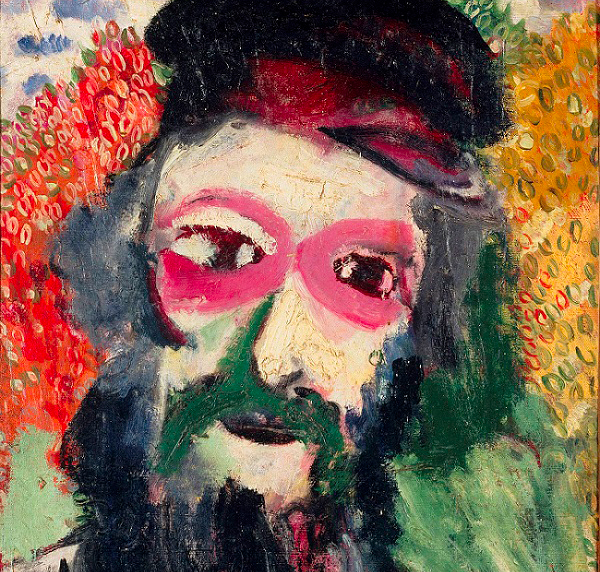

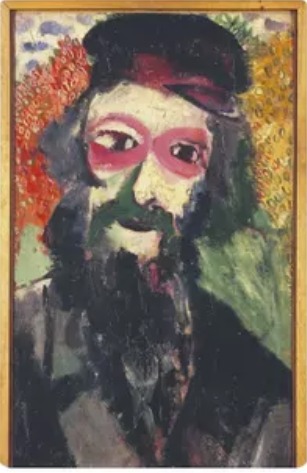

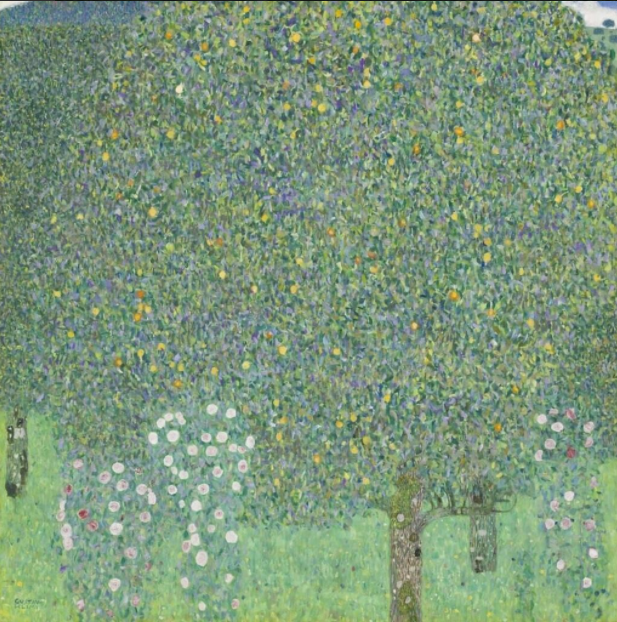

On February 15, the Assembly voted unanimously for a bill acknowledging the restitution of 15 works looted by the Nazis from Jewish collectors, which will come out of the national collections within a year. Symbol of these returns, Le Père by Marc Chagall (1911), seized in Lodz in 1940, during the looting of the apartment of the Polish luthier David Cender, has had an astonishing journey.

An Auschwitz survivor who was dispossessed of all his possessions after the war, David Cender (1899-1966), who had settled in France in 1958, had filed claims for compensation with the Federal Republic of Germany as early as 1959. Although the spoliation of the painting was officially recognized by the Brüg Commission in 1972, almost 20 years after his claim, the musician never saw The Father again in his lifetime, having acquired it in 1928 from the dealer Abe Gutnajer in Warsaw. Nearly 80 years after the theft and disappearance of the painting, the Canadian company Mondex Corporation, which specializes in tracing the provenance of looted property, investigated for 7 years to find its whereabouts. By collaborating from 2019 with the Ministry of Culture’s Mission for the Research and Restitution of Cultural Property Looted between 1933 and 1945, then freshly created and directed by David Zivie, it succeeded in locating the painting in a national collection, namely that of the Centre Pompidou. Kept in its repository for 10 years, it was transferred in 1998 to the Museum of Jewish Art and History, which until recently showed the painting during the exhibition “Chagall, Modigliani, Soutine… Paris for school, 1905-1940”.

© Cender Family Archives.

In donation for the Chagall estate…

Returning a MNR (National Museums Recovery), that is to say, one of the works looted and repatriated from Germany after the war is one thing (which is done more simply, by administrative act), returning a non MNR work is another, which imposes this removal from public collections. A huge change is taking place at the governmental, legal and jurisprudential level,” says lawyer Melina Wolman, who has followed the case in France for Mondex. We are witnessing a global movement on the part of institutions, which increasingly favor restitution. According to her, this is evidenced by the responsiveness of the Centre Pompidou and the MAHJ, who were immediately willing to cooperate: “When I contacted them a year and a half ago to report on our research, they were initially astonished, because the painting was the result of a donation in payment of Marc Chagall’s inheritance tax in 1988. It was therefore a rather unprecedented situation: because the painting had legally entered the national collections, we had to present them with an extremely solid case. Mondex’s research established that Marc Chagall had indeed recovered the painting after the war, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day. It is also assumed that he himself had lost the painting in 1914, when he left France at the outbreak of the First World War.

“By confronting the two museums with the 1972 documents establishing the spoliation, it became undeniable that a restitution process was underway,” adds Melina Wolman.

Mondex’s research established that Marc Chagall had indeed recovered the painting after the war, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

A passage in Italy

Among the other key documents that shed light on the painting’s trajectory are Italian archives relating its passage through Italy during an exhibition at the Museo civico d’arte antica in Turin in 1953, mentioning Marc Chagall as its owner. Another archive from the Wallraf-Richartz Museum reported his visit to Cologne in 1967. For James Palmer, President of Mondex, the moving discovery of a 1962 certificate from David Cender (written as part of the compensation process), describing The Father in great detail, was a real turning point:

“When we were able to access a color photograph of the painting, we immediately realized that David Cender’s description matched perfectly with what we had on our screen, especially when he described in detail the outline of the figure’s eyes. We were very happy with this important discovery. There was no way we could be mistaken. After years of investigation, James Palmer and Melina Wolman went to the MAHJ a few days ago to finally face the painting that they had only been able to examine on computer until now. “It’s a touching representation of Chagall’s father, who at first glance portrays him as this serious orthodox father, but whose playfulness is evident, and can be detected in the details, particularly in the position of the hat,” says James Palmer.

The slowness of the procedures: this is what the heirs of spoliated persons have been reproaching France for years. Each case is unique, and the particularities of each case, as well as the grey areas, sometimes make it difficult to clarify the situation.

Towards an acceleration of restitutions?

For Melina Wolman, this happy outcome would not have been possible without the good understanding of French museums and the determination of her contacts at the Ministry: “We were able to count on the renewed commitments of Laurent Le Bon to facilitate this process by keeping to our timetables.

The declassification procedure that followed, with the vote of the law in Parliament, is quite unprecedented. The vote of such a law takes a lot of time, and it is often a lot of suffering for the families”. The slowness of the procedures: this is what the heirs of spoliated persons have been reproaching France for years. Each case remains unique, and the particularities and the grey areas sometimes make the situations difficult to clarify.

This is illustrated by the case of the eleven drawings and one wax that belonged to the Dorville family, whose descendants had, before the bill was passed, challenged the ambiguous terms of the bill, which proposed that twelve works acquired by the Louvre in 1942 be “returned” to them. The “questionable context” of their purchase was set out in black and white in a communiqué issued by the Ministry on February 16, and the spoliation was finally officially established. Thirteen of the fifteen rightful claimants have been formally identified by the Commission for the Compensation of Victims of Spoliation (CIVS), created in 1999. Last January, Roselyne Bachelot said she was in favor of a “framework law” to facilitate the removal of cultural property from the public domain, which would avoid the cumbersome process of a special law such as the one passed in February.

A promise that the descendants of looted collectors hope will be kept. For its part, the Museum of Jewish Art and History will exhibit The Father, accompanied by an explanatory scenography, from February 23, for an undetermined period of time, until it leaves its walls for good.

According to Melina Wolman, “the exact date of the handover of the painting has not yet been decided, but we hope that it will take place before the presidential elections, with a ceremony in the presence of David Cender’s descendants, who will travel from Israel.

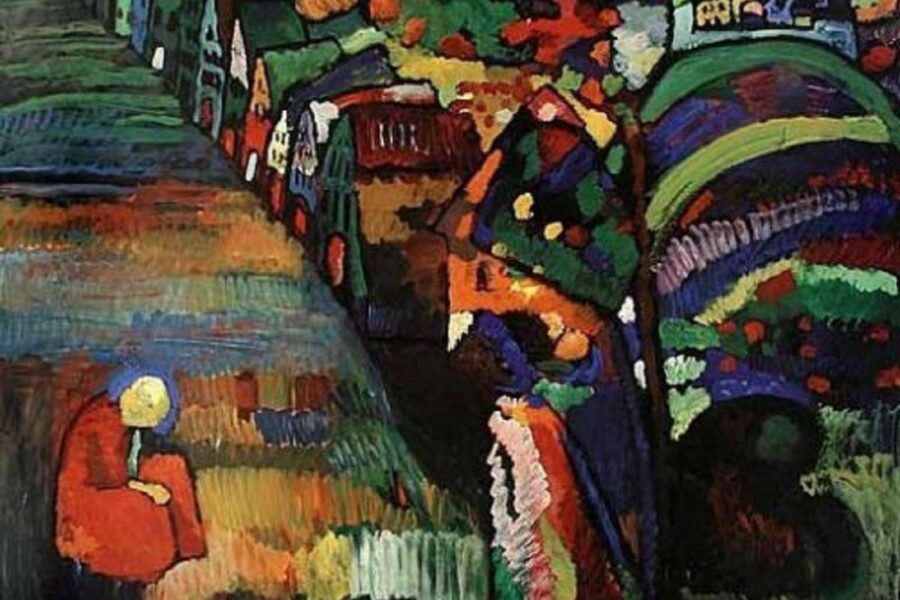

circa 1905, oil on canvas, 109,2 x 109,2 cm.

This painting is part of the works concerned by the bill voted in the Assembly.

DR.