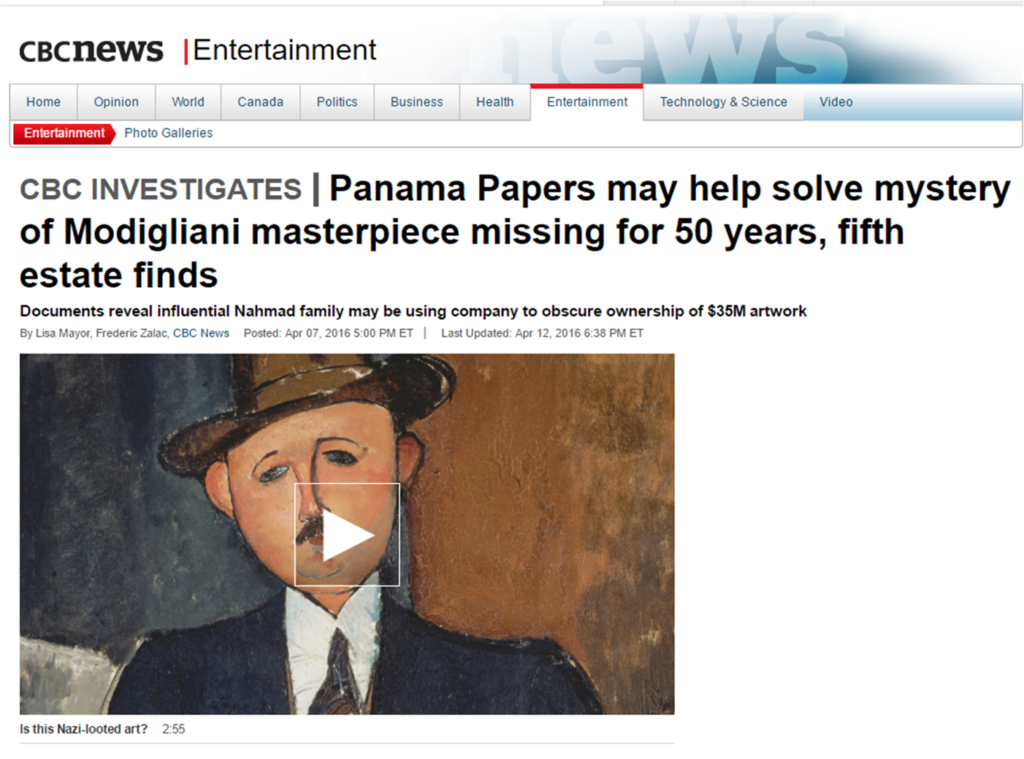

A Modigliani masterpiece estimated to be worth $35 million is in the middle of a decades-long controversy over its rightful owner. Now, a massive leak of 11.5 million documents known as the Panama Papers contains secret documents that may help solve part of the mystery of the masterpiece called Seated Man With A Cane.

The Panama Papers reveal that a powerful family of international art dealers may be using a Panamanian-registered company to obscure its ownership of the Modigliani painting that is at the centre of a high-stakes court battle.

The documents were revealed Thursday through a joint investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the Toronto Star and the fifth estate. They were first leaked to the German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

These revelations appear to have had an immediate impact. According to Le Temps newspaper in Geneva, Swiss authorities — reacting to the Panama Papers revelations by the ICIJ about the Modigliani — executed a search warrant Friday morning at a vast warehouse in Geneva where the painting is being stored, seeking information on the masterpiece.

The family of Jewish art dealer Oscar Stettiner believes the painting belonged to him when he lived in Paris before the Second World War and was looted by the Nazis when they occupied Paris. For five decades after the war, Seated Man With A Caneremained hidden — but in 1996, it made its entry in the world of the ultra-wealthy through an auction. It was sold at a Christie’s in London, reportedly for $3.2 million US, to a little-known corporation called the International Art Center. Then the painting was shown in galleries in London and New York owned by a powerful family of international art dealers — the Nahmads. The Nahmad family won’t reveal the extent of their wealth, but their collection — according to Forbes Magazine — is valued at $4 billion.

The family is not without controversy — in 2013, Helly Nahmad pleaded guilty to operating an illegal gambling business. He was sentenced in federal court in Manhattan to a year in prison and paid a forfeiture of more than $6 million. Now, the Nahmads are being sued in the Supreme Court of New York by Oscar Stettiner’s grandson Philippe Maestracci for the return of the Modigliani painting.

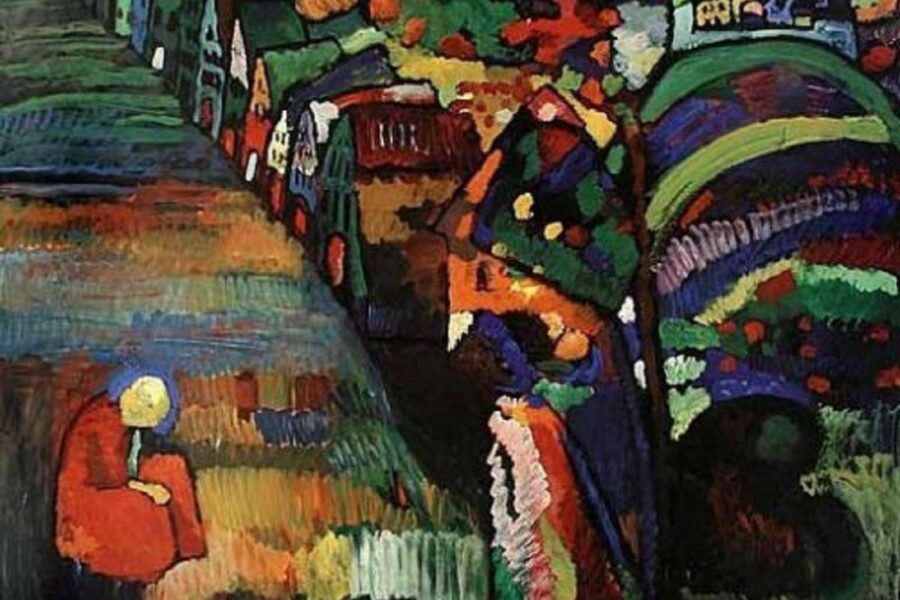

A Seated Man With A Cane was displayed at the Helly Nahmad Gallery in New York City. (CBC) In court filings, the Nahmads claim that while their galleries displayed the painting, they don’t own it. It’s owned by a company registered in Panama called International Art Center (IAC). “Not anyone else in the world including defendants Helly Nahmad owns the painting, says a response filed last year by the Nahmads’ lawyers.

“Davide Nahmad has been sued for a reason I can’t figure out,” New York lawyer Richard Golub told the fifth estate. “The painting is owned by a corporation.”

But secret internal documents found in the Panama Papers reveal thatcorporation — the International Art Center, located in Panama — was established by the Nahmads as far back 1995. In one letter dated 2014, Davide Nahmad describes himself as “the sole shareholder.”

The internal documents include shareholder certificates and corporate registration records.

Shown documents from the Panama Papers by the fifth estate, Golub dismissed their importance in the case.

“I don’t know what the document says and it doesn’t matter what the document says. That document may be superseded. I don’t know what that document means, and I don’t know where you got it. And it doesn’t mean anything,” Golub said. “Who owns IAC is about as relevant to this as, you know, who’s living on Pluto.”

But James Palmer, an art investigator working for the Stettiner family, sees it quite differently.

“This is about getting justice and getting closure and that’s what this is about,” Palmer said. “It’s really simple. The painting was stolen and it needs to be returned to its owner.”

Canadian James Palmer is the founder of Mondex Corporation, a company that helps beneficiaries with the recovery of looted and unclaimed assets. (CBC)

Palmer, a Canadian and the founder of Mondex Corporation, has built a career and a business on finding art looted by the Nazis and returning it to the rightful owners — for a fee.

Palmer says he will now use these newly leaked documents to bolster his client’s claim in court against the Nahmads. The Panama Papers seem to be confirming what he suspected about art magnate Davide Nahmad.

“He is controlling the purchase of that painting,” Palmer said. “He’s controlling that painting right now…. He’s the one in control, he’s pulling the strings. So that’s not a sideshow. That’s the main puppeteer, in action.”

The Nahmad family is also contesting the claim by Stettiner’s grandson that the family ever owned the painting.

“This is a proofless case,” Golub said. “I don’t think it belonged to his grandfather, and I don’t think he’s got a claim.”

It’s difficult, almost a century later, to trace the ownership of the Seated Man that Modigliani painted in 1918.

‘You’ve got a photograph of the painting, the same painting that we’re pursuing and you’ve got a reference to Oscar Stettiner’s ownership of that painting.’- James Palmer

The painting was shown at the famous art exhibition Venice Biennale in 1930. In the files from that exhibit, Palmer found a photograph of the painting and a catalogue that said it was from the Stettiner collection — plus a letter copied to the Biennale where Stettiner is referred to as the “propriétaire,” or the owner of the painting, at the time.

For Palmer, this is compelling evidence bolstering Stettiner’s family claim. “You’ve got a photograph of the painting, the same painting that we’re pursuing and you’ve got a reference to Oscar Stettiner’s ownership of that painting,” Palmer said.

Whatever the ownership of the Modigliani in the 1930s, things got murky afterwards. Two big questions remain: Did ownership of the painting change? And where did the painting go?

History of the mystery

When the Nazis occupied Paris in the 1940s, Jews were targeted, arrested and deported. Their possessions were stolen and sold to fuel the German war effort.

In the National Archives of France, there is an inventory of items from Stettiner’s gallery in 1940, treasures forcibly sold in four auctions during the war — one of which took place at Stettiner’s gallery near the end of the war.

Those records show a Modigliani — no name was given. But there is a puzzling detail. That Modigliani sold for a paltry 16,000 francs.

Such a low price disproves any Stettiner family claim to a Modigliani masterpiece, says Golub.

“I don’t think there’s any way in hell you can buy a Modigliani for 16,000 francs in 1944, 1943, 1942, any time like that,” Golub said. “Commercially, absolutely too low to be a Modigliani.”

In this legal battle, the Nahmad family has retained New York lawyer Richard Golub. (CBC)

But Willi Korte, an art expert who specializes in Nazi stolen art, says there’s a crucial detail to consider: The date of the sale was July 1944. “You have to keep in mind in July that it’s after D-Day in Normandy so the Allied forces were already on French soils advancing towards Paris,” Korte said. “So, this may very well have been a price, the only price that you could realize at that time under those circumstances.”

One thing is known for certain. After the war, Stettiner filed a claim for his stolen treasures including “a Modigliani” — which he described as a “portrait of a man.”

Where’s the proof?

Golub says that even if the document is accurate, there is no proof that that particular Modigliani was Seated Man With a Cane. In 1946, a Paris court did indeed rule in favour of Stettiner’s claim, but it came too late. The Modigliani had allegedly been sold off to an unknown American soldier. In 1948, Oscar Stettiner died in a small village in the south of France, never having seen his painting again.

Davide Nahmad, a Jew himself, says he would never accept art that was looted by the Nazis. Davide Nahmad says he would not sleep at night if he knew that he owned ‘a despoiled object.’ (Lionel Cironneau/Associated Press)

“I will not sleep at night if I know that I own a despoiled object,” Nahmad said. “It brings bad luck. It’s an enormous crime. There’s one thing that I believe with all my heart: you must not make money with the suffering of war victims.”

When pressed on whether he’d give it back, he makes a most intriguing promise.

“I think I would,” Nahmad said. “If they can prove that this painting belongs to them then they can go to court with the sales receipt, the painting was sold on such a date, it is this painting.”

If there is a sales receipt, will it ever be found or is it lost forever in the fog of war? The Seated Man is now destined to be fought over in court for many more years.

And the final irony: It can’t be seen in any gallery in the world. The Nahmads have locked it up in a giant warehouse in Switzerland — along with thousands of other priceless pieces of art.

Philippe Maestracci is the sole living heir of Stettiner. As this battle over the masterpiece rages on, Maestracci has just one reason for persevering.

He was reached at his home in La Force, France, where he told reporters, “I do this for the memory of my grandfather.”