[THIS IS AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE ORIGINAL GERMAN ARTICLE “Mitgefühl darf nichts kosten” PUBLISHED ON THE Süddeutsche Zeitung ON DECEMBER 17, 2020] (https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/kandisky-ns-raubkunst-restitution-1.5151284)

December 17, 2020, 4:50 p.m. Nazi looted art

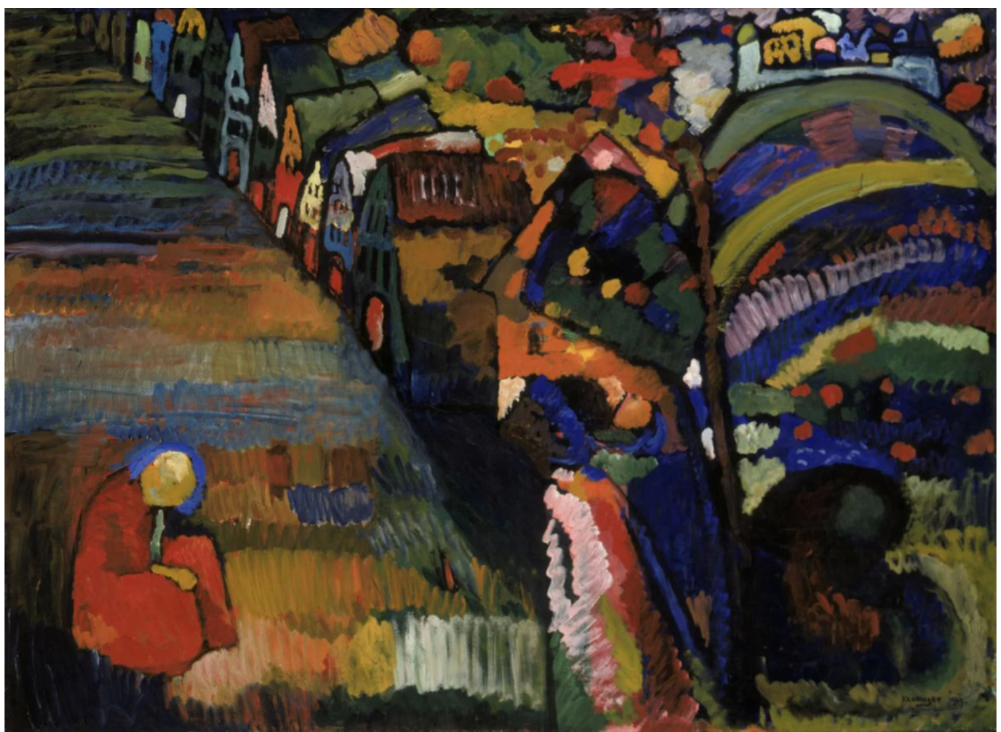

Wassily Kandinsky painted the “picture with houses” in 1909, later it was bought by the Jewish Lewenstein family. Their heirs are demanding the image back from the city of Amsterdam.

(Photo: picture alliance / dpa / Collectie S)

In the Netherlands, the interests of museums are offset against the claims of disenfranchised Jews. A court has now ruled against the return of a Kandinsky painting. A similar case will soon be negotiated in Germany.

From Kia Vahland

In the Netherlands there is a dispute about looted art – and it’s not just about the question of whether this or that work of art in a museum was stolen by the Nazis, as in this country. It is also debated whether the rights of today’s public do not outweigh that of the heirs of Jewish victims. This “weighing of interests” is provided for in the statutes of the Dutch Restitution Commission, and it means that there are more concerns about returning them to art-historically important and therefore expensive paintings than to less important ones.

The commission recently decided not to hand over Wassily Kandinsky’s “Picture with Houses” from the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum to the heirs of the Lewenstein family, who owned the work until 1940. In occupied Amsterdam it was sold at an auction in the vicinity of Nazi greats such as the dealer Alois Miedl. It is uncertain who submitted it there; however, there is nothing to indicate that the Lewenstein family had voluntarily parted with the plant. With proceeds of just 160 guilders – the painting had already brought in 500 guilders in 1923 – this is also unlikely, especially since the family, some of whom already lived abroad, did not receive the sum.

The heirs benefited from the fact that the case is now also on the agenda of Dutch politics

The heirs, represented by the Canadian art search agency Mondex and the lawyer Axel Hagedorn, challenged the Commission’s decision in court. They benefited from the fact that the case is now also a concern for Dutch politics. The responsible ministry had set up a committee that was supposed to evaluate the work of the commission in general and came to the conclusion that the museum was valued as a public place and a guardian of cultural heritage – but if the descendants of the stolen and blackmailed make legitimate claims, the reparation of injustices must have priority . No “balancing of interests”, therefore, but the advice to return to the former, more liberal restitution policy of the Netherlands.

So far, however, this is only a recommendation – the Amsterdam Regional Court did not have to orientate itself. And didn’t. On Wednesday the judge ruled that the Restitution Commission was right on all points, including the idea that the public interest outweighs that of the injured party. Kandinsky’s work is to remain in the museum.

The city of Amsterdam announced that it would be declared on a board in the museum hall and that “this painting will forever be associated with a painful story”. But as far as to do without an important work of art and a presumed double-digit million amount, the sympathy does not work. The Stedelijk Museum told the SZ that they only contributed the research and accepted any outcome of the proceedings. That doesn’t sound like much regret about one’s own role in the war and the years after that, when the Lewensteins found little support. The heirs’ lawyer announced that he would appeal.

How the process continues will also have an impact in Germany. At the 1940 auction in Amsterdam, a second, even more important work by Kandinsky was auctioned: “The Colorful Life”, today a highlight in the Lenbachhaus in Munich, owned by the Bayerische Landesbank. It also once belonged to the Lewenstein family; it entered the 1940 auction through a restorer who cooperated with the museum. The buyer was the modernist Salomon Slijper, who, being a Jew himself, sent a middleman. Later, the story circulated in the Netherlands of how Slijper and the then museum director of the Stedelijk, David Röell, are said to have agreed: everyone could have bid on just one of the two Kandinskys to keep the price low.

The Lewenstein’s heirs also lay claim to “Das Bunte Leben” (The Colorful Life); the case is currently before the German Limbach Commission, which makes recommendations on Nazi-looted art. In Germany there is no “balancing of interests” at the expense of the victims. The loss for Munich and the German museum landscape would be immense if Kandinsky’s main work had to be restituted in the end. However, this in no way justifies simply keeping art that was presumably sold under duress . Should the Limbach Commission generally recognize the claims of the Lewenstein descendants, there would be a way out of the dilemma: One would have to find the necessary money.