After a chance discovery, the grandson of a Jewish art dealer learned that a valuable painting he believed the Nazis had looted from his grandfather might now be in the hands of one of the art world’s most influential families. Proving it has been another matter.

The work, by Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani, is known as “Seated Man with a Cane.” Modigliani, a young, impoverished alcoholic, died of tuberculosis almost a century ago; his paintings today sell for as much as $170 million. The portrait of a dapper man with a mustache perched on a chair, hands resting upon his walking stick, may be worth $25 million.

Investigators traced the painting to a clan of billionaires that bought the work at auction in 1996. Lawyers working for the grandson sent a letter to the Nahmad Gallery in New York, stating that the painting belonged to the grandson, who was entitled to its return. They requested a meeting to discuss the matter. The gallery failed to respond, according to court documents. The grandson sued. Four years later, the two sides’ lawyers are still fighting it out.

The Nahmads have insisted in federal and state court in New York that the family does not possess the Modigliani. An offshore company called International Art Center, registered by a little-known Panamanian law firm, does.

But secret records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners suggests that the statement is a legal sleight of hand designed to obscure the true owners of the painting.

The records, more than 11 million documents in all, come from the internal files of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm that specializes in building corporate structures that can be used to conceal assets. Dating from 1977 through 2015, the files include the biggest known cache of inside information on the connections between the international trade in art and offshore secrecy jurisdictions. The records paint a picture of a thinly regulated industry where anonymity is regularly used to shield all kinds of questionable behavior.

The Nahmad family has controlled the Panama-based company, International Art Center, for more than 20 years, the records show. It is an important part of the family’s art business. David Nahmad, the family leader, has been the company’s sole owner since January 2014.

When confronted with documentation that showed the Nahmads owned International Art Center, David Nahmad’s lawyer, Richard Golub, said “whoever owns IAC is irrelevant. The main thing is what are the issues in the case, and can the plaintiff prove them?”

The central question, Golub said, was whether the grandson can demonstrate this specific painting was stolen from his grandfather. Despite years of battling in court, it’s an issue that has received scant attention from a judge, since both sides have been fighting over who currently owns the painting.

Mossack Fonseca not only helped the Nahmads establish International Art Center in 1995, it provided many of its other clients with the tools to secretly carry out high-end art transactions worldwide for works by artists such as Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Chagall, Matisse, Basquiat and Warhol.

Other well-known art collectors with companies registered through Mossack Fonseca include Spain’s Thyssen-Bornemisza clan, Chinese entertainment magnate Wang Zhongjun and Picasso’s granddaughter, Marina Ruiz-Picasso.

Zhongjun did not respond to a request for comment. Ruiz-Picasso declined to comment. Brojia Thyssen, through a lawyer, acknowledged having an offshore company but said it was fully declared with Spanish tax authorities.

The firm’s records mention enough art to fill a small museum. Along with crucial new evidence in the legal battle over the Modigliani, there are clues in Mossack Fonseca’s files to the mystery of the missing masterpieces of a Greek shipping magnate and previously unknown details behind one of the 20th century’s most famous modern art auctions.

The documents reveal sellers and buyers of art using the same dark corners of the global financial system as dictators, politicians, fraudsters and others who benefit from the anonymity these secrecy zones offer.

In recent years, as art prices have grown dramatically, transactions are often obscured by the use of offshore companies, front men, free trade zones, manipulated auctions and private sales. While secrecy may be exploited legally to avoid publicity, limit legal exposure or ease operations across borders, it can also be employed for nefarious purposes, such as evading taxes and hiding shady ownership histories. Since art is easily transportable, expensive and poorly regulated, authorities fear that it is often used for money laundering.

Boom times

The current art market boom — and its connection to the secrecy zones within the global financial system — offers more evidence of the spectacular rise of the super rich. Art has become a valuable asset for a global elite eager to stash their money in safe and secluded harbors. In 2015, sales of art exceeded $63.8 billion, according to trade publication the TEFAF Art Market Report, with top-dollar art experiencing the greatest growth.

Total billionaire wealth allocated to art was estimated to be $32.6 billion in 2013.

“The single best driver of the art market is accumulated wealth,” says Michael Moses of Beautiful Asset Advisors, which tracks art sales. “If high-end wealth is increasing at a faster rate than any other kind of wealth — which it is — these people have excess money to spend on art.”

Roughly half of art transactions are private, strictly between sellers and buyers, the TEFAF report estimates. There is little public information about these sales. The rest are done through public auctions, which provide some transparency in regards to price but usually still allow buyers and sellers to remain a mystery, Moses says.

When high-dollar art changes hands, it often lands in a free trade zone known as a freeport. As long as art is housed in the freeport, owners pay no import taxes or duties. Critics worry the freeport system can be used to dodge tax or launder money since precise inventories and transactions are not tracked. According to the international professional services firm Deloitte, 42 percent of art collectors it surveyed said they would likely use a freeport. The oldest freeport, with the most art, is in Geneva. Its complex of storage facilities is said to contain enough treasure to rival any museum in the world.

Natural Le Coultre, a company owned by Yves Bouvier, rents almost a quarter of the space in the Geneva freeport. Bouvier is also a primary owner of other freeports in Luxembourg and Singapore and a consultant to a facility under construction in Beijing. These interests have earned him the title “the King of the Freeports.”

But it is Bouvier’s activities as a middleman in private deals that have made him the talk of the art world and a target for civil suits. Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev has filed complaints against Bouvier in Monaco, Paris, Hong Kong and Singapore, accusing him of fraudulently marking up the prices of paintings before selling them. After reviewing the claims, a judge in Singapore lifted a freeze on Bouvier’s assets and a judge in Hong Kong followed suit. Bouvier has strongly denied the charges.

Not surprisingly, given the number of billionaires and art dealers who use Mossack Fonseca’s services, both men are clients of the firm.

The law firm’s records show at least five companies connected to Bouvier, although none appear to be related to the Rybolovlev case.

His antagonist, Rybolovlev, has two.

Rybolovlev declined to comment. A representative for Bouvier said his client used offshore companies for well-established legal purposes.

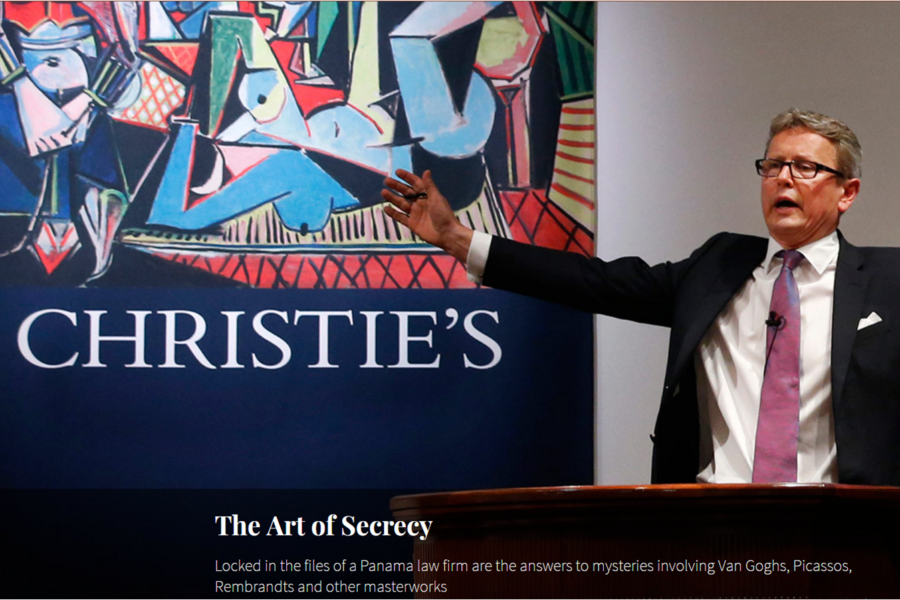

The auction game

Many trace the art market’s wild enthusiasm for modern art to a sale on a Monday evening in November 1997. Held at Christie’s in New York, the auction of the Victor and Sally Ganz collection produced record valuations for paintings and proved a milestone in the transformation of art into a global commodity.

“All of a sudden the game was afoot with the Ganz sale in a way that hadn’t happened before,” says Todd Levin, director of Levin Art Group, a New York-based art advisory firm. “It was like a steroid injection to the market.”

The full story behind the Ganz auction has never been revealed. The leaked documents show it involved hidden interests and one of the art world’s favorite offshore middlemen, Mossack Fonseca.

The Ganzes were collectors of works by Pablo Picasso, early champions of Frank Stella and friends and patrons of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Eva Hesse. After the couple died, their children were forced to sell a collection that had adorned the walls of their childhood home.

It had cost the Ganzes about $2 million over 50 years to assemble. In one evening, the collection sold for a record $206.5 million.

Unknown until now is that the Ganz heirs appear to have sold the collection months before the auction. The key player in the transaction was a corporation based on Niue, a speck of an island in the South Pacific. The company was named Simsbury International Corp.

Simsbury International appears to have been created solely for the Ganz transaction. It was incorporated in April 1997. A month later it purchased the collection. Simsbury’s registered agent was Mossack Fonseca. Employees of the Panamanian law firm served as Simsbury International’s “nominee” directors, stand-ins who controlled the company on paper but who exercised no real authority over its activities. These paper directors signed agreements on the company’s behalf with a bank, an auction house and an art shipping company.

Ownership of the company was held through “bearer shares.” These are simply certificates that allow whoever holds the paper to anonymously transfer or claim their value. Today, they are banned in many countries because of their usefulness to those who want to engage in tax evasion and money laundering.

In a deal struck on May 2, 1997, Simsbury International bought the most valuable of the Ganz paintings for $168 million from Spink & Son, the London auction house then owned by Christie’s, according to the leaked documents.

A representative of the Ganz family declined to answer questions from ICIJ about the specific details of the auction transaction.

The sale came with a side-deal. If the auction for the works brought a higher price, the owner of Simsbury International and Spink & Son would share in the difference.

The man who had power of attorney for Simsbury, and thus exercised control over the company and its bank account, was British billionaire Joseph Lewis. Then the richest man in England, Lewis made his fortune betting on currency movements. He was also Christie’s largest shareholder.

The Ganz catalog stated “Christie’s has a direct financial interest in all property in this sale,” but the terms of that interest were never explained.

Lewis had made a bet that would pay off in multiple ways.

The Ganz auction would help turn 1997 into one of Christie’s biggest years for sales up until then. The auctioneer raked in more than $2 billion that year.

Lewis did not respond to a request for comment.

One of the most expensive paintings sold at the Ganz auction was Picasso’s “Women of Algiers, version O.” It’s one of a celebrated series of fifteen paintings Picasso made in the mid-1950s. In addition to “O,” the Ganz auction featured versions “M,” “H,” and “K.”

Bidding on the works were members of the billionaire Nahmad clan. David Nahmad went home with version “H,” adding it to what is considered one of the largest collections of Picassos in private hands.

An art dynasty

The Nahmads began as a banking dynasty of Sephardic Jews from Aleppo, Syria. In 1948, Hillel Nahmad relocated his wife and eight children to Beirut.

Three of his sons — Giuseppe, David and Ezra — eventually moved to Milan and, by the early 1960s, had become active art dealers. Giuseppe, the patriarch of the family, had a taste for expensive sports cars and, according to his brother David, once dated Rita Hayworth. He also pioneered treating the art business like a stock market, buying and holding paintings until exactly the right time to sell to maximize profit.

He died in 2012. David assumed the mantel of family leader. He and his older brother Ezra both named their sons Hillel after their grandfather. The two sons both go by Helly. Together the four continue the family business.

The two surviving brothers are worth a combined $3.3 billion, according to Forbes. They live in Monaco, among other locales. In addition to currency trading and art dealing, David Nahmad is also a championship backgammon player. Each son has a namesake gallery. Ezra’s son has the Helly Nahmad Gallery in London and David’s offspring, an identically named one in New York.

The Mossack Fonseca records indicate the Nahmads were early adopters of the benefits of offshoring art.

articles/05Art/160407-art-06.jpg

Fine art dealer and billionaire David Nahmad. Photo: AP Photo / Lionel Cironneau

Giuseppe Nahmad registered International Art Center S.A. in 1995 through the Swiss bank UBS and the Geneva office of Mossack Fonseca. It may have existed in another form prior to that date. A document in the Mossack Fonseca files mentions International Art Center acquiring the pastel “Danseuses” by Edgar Degas in October 1989.

The Nahmads’ business, which stretches across jurisdictions and blood ties, is tailor-made for offshoring. With the Nahmad principals based in three countries, galleries on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean and most of the paintings stashed in Switzerland, the family requires the kind of legal siloing made possible by offshore companies.

International Art Center is not the family’s only corporate entity with Mossack Fonseca. Giuseppe Nahmad also created Swinton International Ltd., which was registered in the British Virgin Islands in August 1992.

The offshore entities are interconnected, their use a family affair. Giuseppe Nahmad had power of attorney over International Art Center’s UBS bank account as early as 1995. David and Ezra could also sign for the company’s bank account at UBS. For a company bank account with Citibank two years later, Giuseppe co-signed with his brother Ezra Nahmad, the documents show.

In 1995, Swinton International authorized David Nahmad to negotiate the sale of five paintings it owned — an oil on panel by Picasso, “Danseuses” by Degas, two oils on canvas by Henri Matisse and an oil on canvas by Raoul Dufy. Some of the paintings subsequently went on auction at Sotheby’s, identified as being from a “private collection.” Two of the paintings had been the property of International Art Center.

International Art Center’s ownership was initially held in bearer shares, making it impossible to tell who actually owned it. In 2001, a board resolution by Mossack Fonseca nominee directors created 100 shares in the company and granted them to Guiseppe. In 2008, those hundred shares were reassigned in equal portions to David and Ezra Nahmad. A year later, Ezra split his shares with his son Hillel. David did not do the same with his son.

A hint of tension between David and his son surfaced in 2007, in a rare profile of the family in Forbes. The article described David as “frowning” as he remarked, “My son likes publicity a lot. I don’t like publicity.”

His son Helly’s extracurricular activities could have made him an unsuitable shareholder of International Art Center. Like his uncle Giuseppe, Helly had big appetites. The tabloids charted his exploits: models for girlfriends, a floor of multi-million dollar apartments in Trump Tower, movie star pals and high-stakes gambling. Given the family history, none of that was likely a problem until the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York secured an indictment against him in April 2013 for his leadership role in an alleged $100 million gambling and money-laundering ring with ties to Russian gangsters.

Wiretaps in the case caught him discussing how his family art business could be used to hide money. “[S]ometimes a bank needs a justification for a wire, right?” he said, according to a conversation from March 2012, quoted in the government’s sentencing memorandum. “We can just say, Ohh, you are buying a painting. If they need justification, you know what I mean? You just be like, Oh yeah, I bought a, you know, Picasso drawing or something.”

It was never proven in court that the behavior discussed took place. The conversation did not factor into the ultimate charge and the Nahmads’ lawyer said in an interview it has nothing to do with the Modigliani case.

Helly Nahmad pleaded guilty to operating an illegal gambling business in November 2013. A judge sentenced him to a year and a day in prison. He also agreed to forfeit $6.4 million and relinquish rights to a painting by Raoul Dufy. He served five months.

Missing art

The Nahmads are not the only prominent art collecting clan that has found their offshore holdings embroiled in legal actions.

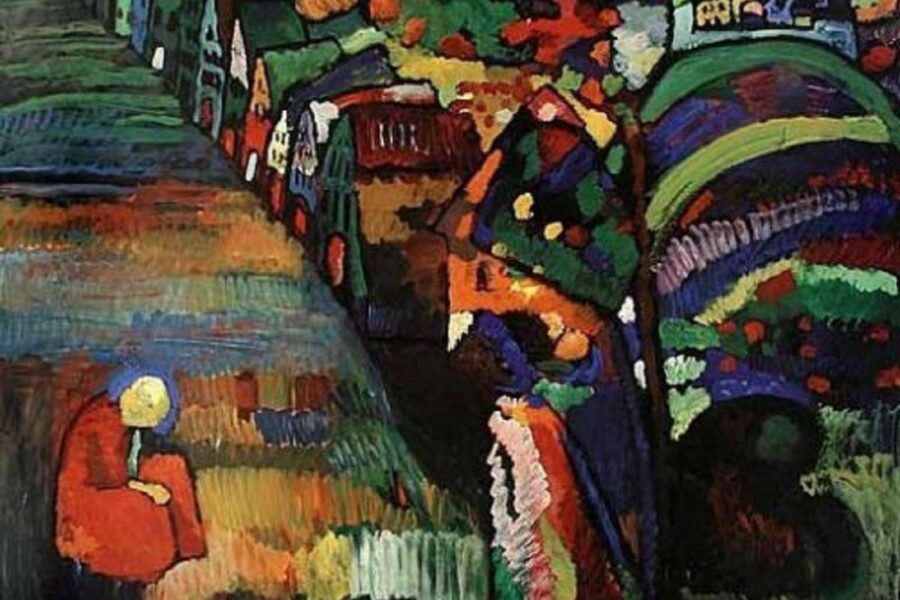

The Mossack Fonseca data provides new insight into a legal dispute involving the Goulandris family, a Greek shipping dynasty that is in the middle of a fight over what happened to 83 missing art masterpieces.

“All told this is about $3 billion worth of paintings,” Ezra Chowaiki, a gallery owner who is helping to bankroll one of the legal claims, told ICIJ in an interview. “It could be the largest collection of missing paintings in history.”

Two lawsuits and a criminal investigation are underway in Lausanne, Switzerland, to try to determine the whereabouts and ownership of the art collection. The cases feature a sprawling and wealthy family at war with itself, shell companies based in Panama, allegations of a forged document and paintings by the likes of Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso.

articles/05Art/160407-art-10.jpg

The Goulandris clan with Chagall’s ‘Le violoniste bleu’ in the background.

Some of the paintings have been sold. The seller did not want the history known. In a $20 million sales agreement found in the Mossack Fonseca files for one of the Goulandris paintings, Van Gogh’s “Nature Morte aux Oranges,” there is a section about confidentiality. It forbids revealing “the identity of the parties to this Agreement (including the identity of the Seller’s sole shareholder)” and “any information or documentation pertaining to the Provenance of the Work and the chain of title.”

The art once belonged to Greek shipping tycoon Basil Goulandris. In 1994, Goulandris died of Parkinson’s disease. After his widow, Elise, died in 2000, her heirs learned the couple’s massive art collection had changed hands years earlier. A Panamanian company called Wilton Trading S.A. owned the paintings.

In 1985, according to Basil’s nephew Peter J. Goulandris, Basil sold the entire collection of 83 paintings for the extraordinarily low price of $31.7 million dollars to Wilton Trading. Despite the sale, the paintings never left the couple’s possession. During this period, Basil and Elise Goulandris lent the artwork to museums and sold pieces to dealers with the provenance listed as if the pieces belonged to them.

Much of what is known about Wilton Trading comes from the court cases in Switzerland. It was created in 1981 but didn’t have directors until 1995, ten years after the sales agreement was supposedly signed. According to a Swiss prosecutor, the paper on which the sales agreement is inked didn’t exist in 1985, and no one has been able to prove that any money changed hands.

Peter J. Goulandris told a Swiss court that his late mother, Basil’s sister-in-law Maria Goulandris, was the owner of Wilton Trading.

Through his lawyer, Peter Goulandris declined to comment.

Elise died without offspring. Her niece Aspasia Zaimis believes she deserves a share of the 83 paintings and is suing the executor of Elise’s will.

In November 2004, anonymous companies set up by Mossack Fonseca started the process of selling some of the Goulandris paintings that Wilton Trading had kept.

articles/05Art/160407-art-09.jpg

Bonnard’s ‘Dans le cabinet de toilette’. Photo: Sotheby’s

Early the next year, at a Sotheby’s auction in London, a company called Tricornio Holdings sold a painting by Pierre Bonnard called “Dans le cabinet de toilette.” Another company, Heredia Holdings, signed an agreement with Sotheby’s to sell a painting by Marc Chagall, “Les Comédiens.” A third company, Talara Holdings, put up for auction a Chagall painting called “Le Violoniste Bleu.” Around the same time, the 1888 Van Gogh depiction of a basket of oranges went to California direct marketing tycoon Greg Renker and his wife Stacey in a private sale. The seller was a company called Jacob Portfolio Incorporated.

Renker did not respond to a request for comment.

All four companies were registered just before the transactions and shuttered shortly afterwards, leaving no public trace of who was behind them. The documents now reveal that all four shared a mysterious owner: Marie Voridis.

One of the transactions provides a clue to the identity of Marie Voridis. On October 22, 2004, Voridis transferred all rights to an oil painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir known in English as “the Seamstress” to Talara Holdings. A few weeks later, Talara Holdings transferred the painting back to Voridis.

In September 2005, a Greek fashion magazine featured the opulent New York apartment of a Greek socialite, Doda Voridis, the sister of Basil Goulandris. Masterpieces by well-known artists decorated the Upper East Side apartment of Voridis, who died in December 2015. In the gossip columns she was always known as Doda but her real name is Marie. Hanging above a handsome armoire in one photo was Renoir’s “the Seamstress.”

War and treasure

The controversy over Modigliani’s “Seated Man with a Cane” began in a time when the fog of war provided the kind of concealment the offshore world offers today. Oscar Stettiner, the Jewish dealer who is alleged to have been the original owner of the painting, fled Paris in 1939, in advance of the Nazis, leaving behind his art collection.

After the city fell, the Germans seized the collection and appointed a French “temporary administrator,” who auctioned off the painting for the benefit of the Nazis, according to legal filings. In October 1944, a U.S. military officer bought the Modigliani in a café for 25,000 francs, according to court documents.

articles/05Art/160407-art-17.jpg

Oscar Stettiner.

In 1946, Stettiner filed a claim in France to begin the process of recovering the painting, court documents filed on behalf of his grandson say. He died two years later, with his petition still pending.

The Nahmad’s lawyer Richard Golub disputes this narrative. He questions whether Stettiner ever owned the painting.

The Modigliani stayed hidden within a private collection until 1996, when International Art Center bought it at Christie’s in London for $3.2 million, according to documents filed in New York courts. The Helly Nahmad Gallery exhibited the painting in London in 1998 and at the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1999. Six years later it was part of a Modigliani exhibit at the Helly Nahmad Gallery in New York.

Toronto-based Mondex Corp., a firm that specializes in recovering Nazi-looted art, discovered the painting’s alleged provenance by accident while looking through files in a French ministry. The company helped initiate the legal battle to return it to Philippe Maestracci, Oscar Stettiner’s grandson. Mondex does not disclose its fee for this service.

On Feb. 11, 2015, the Nahmad’s lawyer in the Maestracci case in New York, Nehemiah Glanc, wrote an email to International Art Center’s attorney in Geneva. Glanc was on record as the lawyer for IAC, but he needed some key facts about the company before he could proceed, the leaked records obtained by ICIJ show.

“Please advise as soon as possible as to who is authorized to sign on behalf of IAC,” he wrote in an email.

If the Nahmads had signed the documents as the owners of International Art Center, they would have likely lost the legal protection the company provided.

The attorney in Geneva put Glanc in touch with Anaïs Di Nardo Di Maio in Mossack Fonseca’s Geneva office. Di Nardo could get the signatures of the Mossack Fonseca nominee directors in Panama as long as Glanc’s clients would pay for it. He agreed.

One document signed by Mossack Fonseca’s nominee directors cost $32.10.

As the case progressed, emails flew back and forth between Glanc and Mossack Fonseca, the leaked documents show. Every time a motion came from International Art Center, the stand-in directors had to sign.

In September 2015, in an austere courtroom in New York, state Supreme Court Judge Eileen Bransten dismissed the Maestracci case. Among her findings, the plaintiffs had failed to properly serve the complaint on International Art Center because they had served papers at the Nahmad Gallery in New York instead of going to Panama. She also ruled that a court-appointed administrator, not Maestracci, was the proper plaintiff. Two months later, the administrator re-filed the case in state Supreme Court in New York as plaintiff.

The new complaint against the Nahmads made another effort to link the family to ownership of International Art Center, which it described as an alter ego of the family enterprise “in a manner so as to confuse and conceal their identities, and hide revenues generated” from the Nahmad family’s art dealing business.

As the case continues on, Modigliani’s 1918 portrait, “Seated Man with a Cane,” is tucked away in the Geneva freeport in Switzerland, another treasure hidden from view.

Contributors to this story: Alexandre Haederli, Juliette Garside, Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer

DID YOU FIND THIS INTERESTING?WORTH SHARI