The Netherlands was once praised for leading the way in returning art that had been looted from Jewish people during the Second World War and added to Nazi collections.

But no longer. After a growing chorus of international criticism for refusals to hand back prize pieces in recent years, a government review has admitted the country needs to show more “humanity, transparency and goodwill” towards the heirs of Holocaust victims.

A report published on Monday admits since 2015, the Dutch have been wrong to weigh up the interests of modern-day museums, where the art has ended up, against those of the rightful heirs.

Dutch culture minister Ingrid van Engelshoven said: “We need to strive for justice, because restitution is about more than giving back a work of art. It is about recognizing an injustice that was done to the original owner:’

The hard-hitting report said while the Dutch were once considered a role model, “that reputation has been undermined” by a number of recent rejections.

Instead of being reunited with family heirlooms of great symbolic, emotional and monetary value, the report said, claimants face legal actions and bureaucracy that seems “inaccessible, opaque and painfully slow”.

At the end of the Second World War, Allied forces returned thousands of objects to the Netherlands, from carpets, crockery and furniture to paintings today worth millions of pounds. Some 3,750 of these objects still remain in a national collection.

Some of the objects were simply looted or confiscated by the Nazis while their owners were sent to death camps, murdered or fled the country; others were sold at a far lower price than they were worth, under duress, something considered a “forced sale” if it happened between May 1940 and the end of the war.

A Dutch restitution committee established in 2001 has assessed claims on a total of 1,620 objects, and 64 per cent were not given to the claimants.

The chairman of the review, Jacob Kohnstamm, said this was not right.

“We think that if you look at the dehumanization, the robbery, the murder of Jews in the Nazi period, this cannot be weighed against the importance of art for a museum

[today];’ he told The Telegraph.

He said it was a “moral obligation” for the Dutch government to research the history of all of its works of art, and reach out to potential heirs.

The report recommends creating a special helpdesk, clear framework for requests and a €3 million, four-year research project to trace the history of looted goods and find the heirs.

“This is very much on the agenda at the moment, in the context of Black Lives Matter and coming to terms with the darker sides of our history;’ said Gert-Jan van den Bergh, a Dutch lawyer who acts on restitution cases.

“It is a matter of truth-finding and taking responsibility for our own deeds:’

For Dutchwoman Hester Bergen, who believes she has definitive proof that her ancestor Johanna Margarete Stem-Lippeman owned the Kandinsky painting View of Murnau with church, now in the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the report is hugely welcome.

“We were delighted;’ she said. “This isn’t about money. This is about justice, especially for my aunt, who is 85:’

A Dutch museum review has previously found that there are at least 173 works of suspicious provenance in their collections.

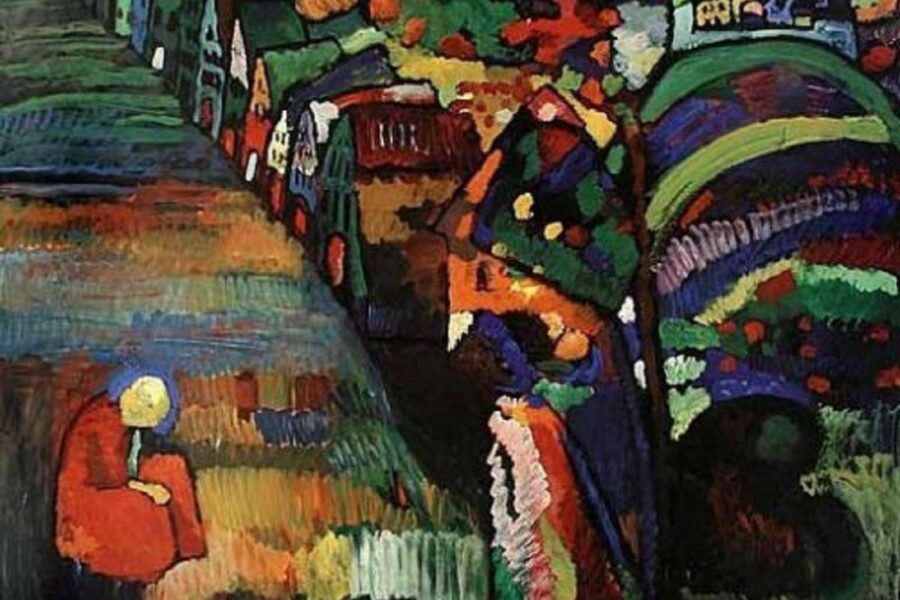

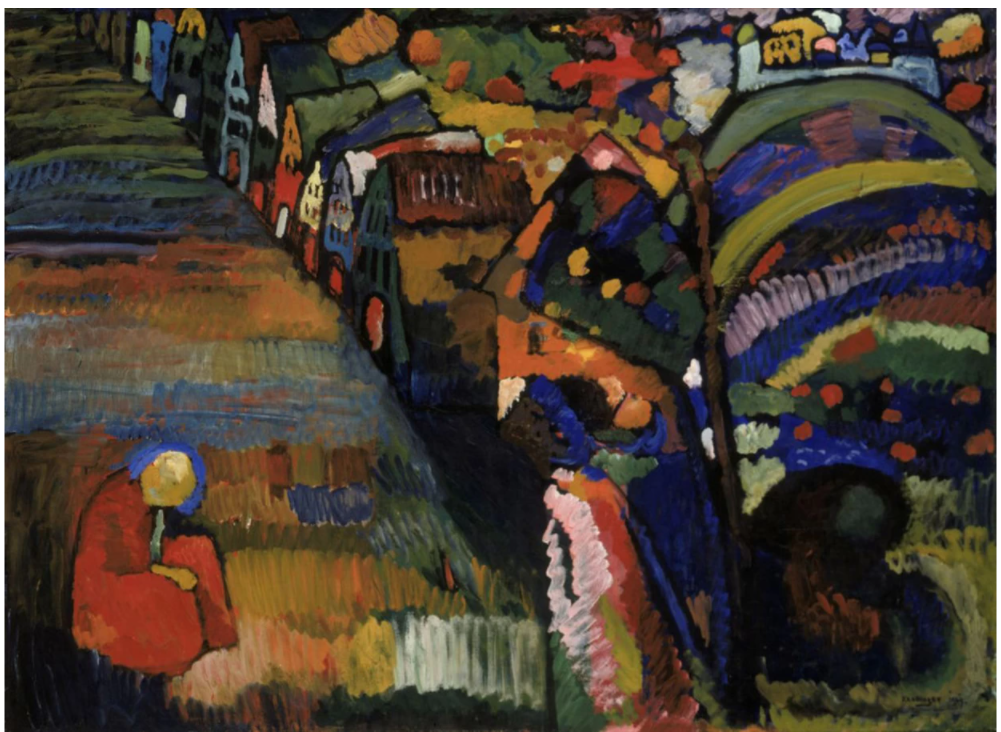

One recent controversy has been over another Kandinsky work, Painting with Houses, in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk museum.

The institution admits it was “possibly an involuntary sale” but has not returned it to the heirs of its original Jewish owner Robert Lewenstein.

A court ruling on the case is expected next week.